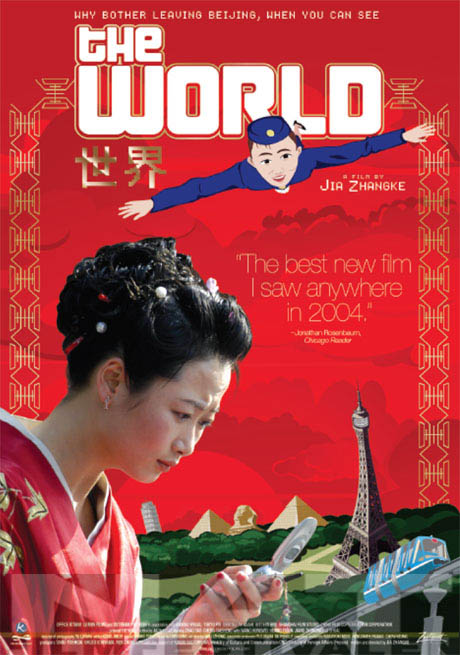

Jia Zhang-ke: The World

I've been wanting to see this film for over a year now, ever since the Chicago Reader's Jonathan Rosenbaum mentioned it in his top 10 for 2004 and again in 2005. The World centers around a Beijing theme park where visitors can "see the world, without leaving Beijing". The young people who work at the park as performers and security guards are mostly recent arrivals from outlying Chinese provinces. They ride a monorail into the park, they perform Indian dance styles in front of a mock Taj Mahal, eat lunch on the top of a fake Eiffel Tower (1/3rd the size of the real thing), or wear kimonos and sip tea outside a traditional Japanese house. Yet none of them have ever left China. Protagonist Tao quips while aboard a 747 that serves as one of the park's exhibits that she doesn't even know anyone that's flown on a plane. Its in this irony that the genius of the film lies. While modern China is becoming a major player in the global economy, its citizens are set adrift in a world that feels cold and alien.

I've been wanting to see this film for over a year now, ever since the Chicago Reader's Jonathan Rosenbaum mentioned it in his top 10 for 2004 and again in 2005. The World centers around a Beijing theme park where visitors can "see the world, without leaving Beijing". The young people who work at the park as performers and security guards are mostly recent arrivals from outlying Chinese provinces. They ride a monorail into the park, they perform Indian dance styles in front of a mock Taj Mahal, eat lunch on the top of a fake Eiffel Tower (1/3rd the size of the real thing), or wear kimonos and sip tea outside a traditional Japanese house. Yet none of them have ever left China. Protagonist Tao quips while aboard a 747 that serves as one of the park's exhibits that she doesn't even know anyone that's flown on a plane. Its in this irony that the genius of the film lies. While modern China is becoming a major player in the global economy, its citizens are set adrift in a world that feels cold and alien.

What struck me about the film was both the stylistic and thematic similarities to the classic work of Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu. Jia even names one of the chapters of the film "Tokyo Story" after Ozu's masterpiece of the same name. But where Ozu focused on changes in Japanese family life in the aftermath of WWII, Jia is concerned with the changes in Chinese society as they evolve towards capitalism. The characters are alienated from each other and from the rest of the world, they spend much of their free time text messaging each other, never making any meaningful personal connections. A group of Russian workers come to the park only to be exploited when their passports are taken away. Their only way out of Beijing is through the sex trade, culminating in a moving scene where Tao recognizes one of the workers at a nightclub and despite the language barrier, their shared tears of commiseration a tacit acknowledgment that they are out of place in the new society. Tao wants to assert her independence as a woman, but this angers her boyfriend, Taisheng, who is trying to hold on to the values of their rural upbringing. Taisheng eventually winds up cheating on Tao with a factory supervisor who has been separated from her husband and sends Tao into depression. For Tao, Taisheng represents her only connection to a home that seems as far away as the exhibits at the theme park and his betrayal severs what tiny threads that still bind her to her past and to a Chinese culture that is fading as the country is brought into the world economy.

Stylistically, Jia's film combines some of the formal elements of Ozu with a few post-modern twists. Each text message sets up an animated vignette that adds to the film's dream-like qualities. Chapters are separated by scenes from a large-scale stage show that the park's workers perform at the end of the day, jolting the film out of its quiet solitude with a modern soundtrack by Lim Giong. These disconnects, and the disconnections between the characters, are what make this such a compelling movie. The ending may seem to some as forced or ambiguous, but the final words contain what I think is an underlying themethroughout and perhaps the most important message: This is only the beginning. Coming from China, Jia's perspective on our world is not grounded in having known only capitalism as a way of life, and as such, The World is a fresh perspective on the trade offs we've made for this global economy and one of the best films of the decade so far.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home